Can PHWR-220 Help India Meet Its Clean Energy Goals?

While small modular reactors and PHWR-220 units offer a nuclear solution, their deployment faces regulatory, logistical, and cost challenges

Can PHWR-220 Help India Meet Its Clean Energy Goals?

Given the marginal cost difference and higher power output, PHWR-700 reactors could emerge as a more practical option. However, the transition will require careful site selection, infrastructure investment, and policy support to ensure India remains competitive in global trade while meeting its clean energy goals

The European Union (EU) has taken a significant step toward fostering greener industrial practices worldwide by introducing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). This policy imposes a carbon tariff on imported goods with a heavy carbon footprint, ensuring that these imports face a carbon price similar to that of EU-produced goods under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS).

Starting in January 2026, the EU will begin imposing carbon taxes on a range of imported goods, requiring cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity, and hydrogen importers to secure CBAM certificates corresponding to their embedded emissions. India, a major player in global trade, exports approximately $8 billion worth of CBAM-covered goods annually to the EU. Consequently, Indian exporters of iron, steel, and aluminium will have to navigate the new regulatory landscape established by CBAM.

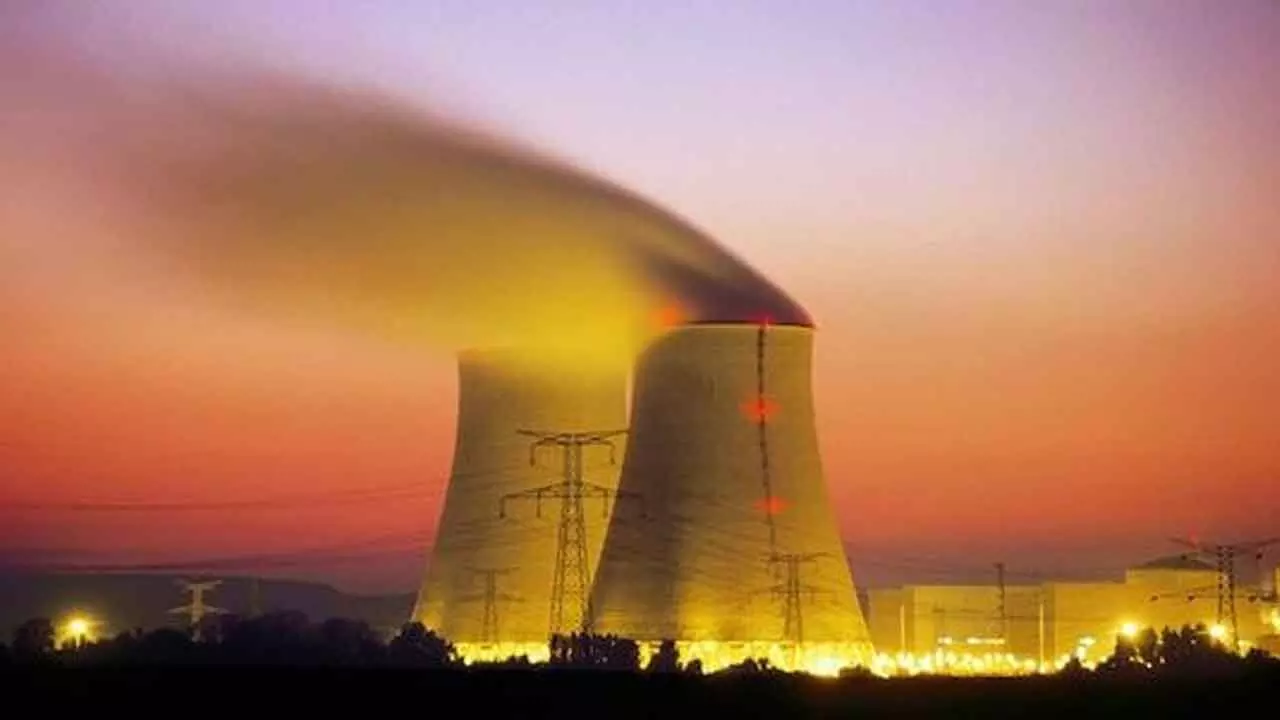

India is the third-largest energy producer in the world and 75 per cent of its energy comes from coal-fired power plants. Heavy industries in India rely heavily on captive power plants, with a staggering 95 per cent of their energy procured from coal. In light of the impending carbon tax on steel and aluminium exports, these industries are looking to transition to cleaner energy sources. More specifically, they are trying to identify green energy power plants capable of generating between 100 MWe and 200 MWe, which can be rapidly established close to existing industrial sites and produce electricity at competitive rates.

Nuclear energy is the only clean alternative for supplying base load power to heavy industries. The problem with nuclear power plants is that they are costly, the land acquisition for the plants is a long and challenging process, and the construction period is very long. Enter small and modular reactors (SMRs), which promise to be relatively low-cost. It is claimed that they can be constructed in factories through an assembly line approach, allowing them to be delivered partly assembled to their final location. This method reduces the on-site labour required and enables efficient commissioning within three years of order placement—provided design and regulatory uncertainties are minimal and supply chains for key components are robust.

India’s experience with 220 MWe Pressurised Heavy Water Reactors (PHWR-220) since the 1970s offers a formidable advantage over other SMR options. With fourteen of these plants already operational, the PHWR-220 stands poised as a ready alternative to traditional coal-fired captive power plants. It is a proven design, and all the design regulatory approvals are in place. There is an established supply chain for all its major components within the country, and there is relatively little uncertainty that these reactors can be constructed within four years and can effectively supply crucial base electricity loads.

What are some difficulties in substituting coal-fired power plants with PHWR-220 plants? The site requirements for nuclear power plants are more stringent than those for conventional ones. The soil must be stable, and the site should be in a location that is not prone to earthquakes or flooding. There has to be an assured supply of cooling water for the plant. An additional safety requirement is creating a 1.5 km radius exclusion zone around the plant. No residential or commercial activity is permitted in the exclusion zone. This requirement will most likely delay setting up nuclear power plants in existing captive power plant locations since conventional power plants don’t have the exclusion zone requirement.

There are a few technical reasons why PHWRs are not the automatic choice for new nuclear power plants. First, they require online refuelling, which puts a significant operational burden on the plant. Secondly, they need an extended shutdown of at least six months to replace their coolant channels after every seven or eight years of operation. Third, each major component of the plant must be brought and assembled at the site. There is no factory pre-assembly possible. In fact, this is true of almost all proposed SMR designs that are 50 MWe or larger. The weight and size of the assembled plant will make it too unwieldy to transport by road. To summarise, the PHWR-220 can be used as a clean energy alternative to coal plants where the site requirements are satisfied. Given the relatively slight difference in cost and footprint, it is more commercially attractive to build a PHWR-700 rather than a PHWR-220. The additional capital cost will be quickly recovered from the extra electricity generated.

(Dr Arvind Kumar Mathur is a nuclear engineer who has worked for many years in India’s strategic submarine program. He is presently the Director of the School of Engineering at DY Patil International University, Akurdi, Pune)